Many winemakers consider it essential for consistency and quality in wine. What is SO2, and why are moves by some to abandon its use so contentious? Simon Woolf takes a balanced view.

What is SO2?

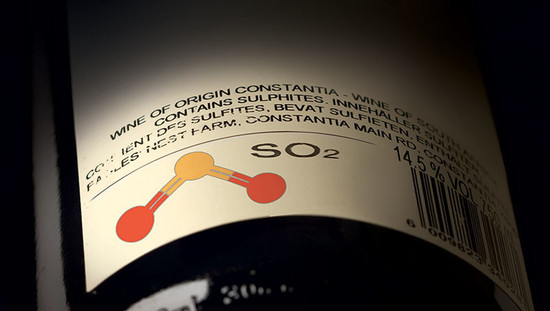

Sulphur dioxide is a compound that contains sulphur and oxygen. It can be produced in its simplest form by burning elemental sulphur, hence the confusing usage of the term ‘sulphur’, when actually SO2 is meant. SO2 is identified in foodstuffs as E220. Two other forms are permitted in wine: E224, potassium metabisulphite; and E228, potassium bisulphite.

Collectively these are referred to as ‘sulphites’, hence the term used on labels.

Toxicity: SO2 is toxic in large quantities; however, the amounts used in wine production are minute. SO2 intolerance is very rare, and most likely to be found in individuals with a pre-existing disorder such as asthma.

I have two bottles here in front of me. Both are Sauvignon Blanc 2012s made by Sepp Muster, a biodynamic grower in Austria’s southern Styria region, both sourced from his Opok vineyard. They taste very different: the first is extraordinarily alive, with concentrated citrus fruit and beguiling complexity; the second feels more muted, somehow more lemonade than lemon.

The difference between the two is a mere 10mg of sulphur dioxide (SO2), added after racking the second bottling. Muster isn’t just trying to prove a point – he’s one of a small but growing niche of winemakers seeking to reduce the intervention and additives used in wine production to close to zero. The spurning of SO2, typically used to prevent oxidation and keep unwanted bacteria at bay, is the final frontier in this quest. It’s regarded as lunacy by most conventional producers, and worshipped like the holy grail in natural wine circles.

Why is opinion so polarised around this topic?

Minimal effects

SO2 definitely has a bad rap when it comes to popular opinion. That could have a lot to do with the terse couplet ‘contains sulphites’, legally required to grace almost all bottles of wine sold in the US since 1988, and within the EU since 2005. Only those with less than 10 parts per million (PPM) are exempted, and here’s the rub – the fermentation process can produce more than that naturally, without any added SO2, meaning that even many ‘no added sulphite’ wines must display the offending words on the label.

Does this mean sulphites are harmful? Probably not, at least not in the minuscule amounts found in modern wines – typically 20-200 PPM. Compare that to a handful of dried fruit, which will have been dosed with anywhere from 500-3,000 PPM. While this amount could theoretically cause an adverse reaction in an asthmatic, it’s extremely rare: sulphite intolerance reportedly affects less

than 1% of the population.

Sulphites are probably not responsible for your hangover either, as Andrew Waterhouse, professor of enology at UC Davis, asserts: ‘There is no medical research data showing that sulphites cause headaches.’

Given the apparent lack of health risks, why do winemakers like Muster insist on reducing their sulphite usage to a bare minimum, or even to zero? Despite its usefulness in slowing oxidation and knocking out harmful bacteria, some believe SO2 also mutes the delicate nuances that express vintage or vineyard character, as Muster proved to me so definitively in our tasting.

Pure ambition

Fellow southern Styrian winemaker Franz Strohmeier has also moved to zero-added SO2. He explains: ‘When we purchased another vineyard, I found a whole load of old bottles that the previous owners had left in the winery. We tasted them and I loved the complexity, the strangeness of the flavours in these old wines. I feel that when you don’t use sulphites, this character comes through more strongly even in young wines.’

Purity is the ultimate goal for many producers on the no-SO2 path. Alaverdi Monastery, in Georgia’s Kakheti region, simply strives to make its wine ‘good enough for God’. In the eyes of the monks, any additive, SO2 included, would render the wine impure and thus worthless. Belgian Frank Cornelissen, who has made wine on the slopes of Sicily’s Mount Etna since 2000, has the similarly straightforward goal to make ‘wine with nothing added’. His imperative isn’t spiritual, but built on the conviction that fine wine can be a totally additive-free product.

Cornelissen believes that the knowledge of how to make wine without sulphites has simply been lost over time: ‘We have to re-learn these skills, which is a slow process.’ Isabelle Legeron MW agrees: ‘Growers are still learning how to make wine with no added sulphur – they only get one go at it every year! Perhaps it’s better if a grower gradually reduces the SO2 each year, rather than immediately trying to make a no-sulphur wine.’

Balancing the risk

There are challenges. When sulphite inputs are forsworn, the risk of bacterial or microbial infection is vastly increased. Obsessive hygiene has to take their place – Cornelissen uses ionised air to clean his cellar. A more ‘laissez faire’ attitude is required when it comes to speed of fermentation, and the yeasts that will be involved. Conventionally, SO2 would be used to see off any wild yeasts on the bloom of the grapes, so that the winemaker can inoculate with his or her choice of laboratory yeast.

Adverse effects vary in their seriousness – wines made without SO2 can have slightly wild, ‘funky’ aromas, which prompt the same love/hate reaction as a ripe/stinky cheese. ‘Mousiness’ is another matter – the curse of the ‘no-SO’ winemaker, this characteristic, finish is undetectable on the nose, but hangs around on the palate and can easily render a wine undrinkable. Once confused with brettanomyces, it’s now recognised as a completely separate problem.

How and why mousiness develops is still only loosely understood, as wine scientist Geoff Taylor of food and drink research company Campden BRI explains: ‘To the best of my knowledge, very little work has been done matching the taint with the compound.’ He clarifies: ‘The (lactic) bacteria can remain dormant for years and when conditions permit (sufficiently low free SO2, warmth), they will grow. And growth is slow.’ The risk is increased by poor hygiene in the winery or damaged grapes. As Taylor implies, this can cause severe bottle variation – another tricky factor to explain to wine drinkers used to more consistent, industrially made wines.

Producers working in this extreme fashion tend to be small, artisanal, and loosely allied under the ‘natural wine’ banner. There are exceptions – Stellar winery in South Africa’s Western Cape is a large-scale producer that very successfully introduced a no-SO2 range of wines to the UK’s supermarkets in 2008.

No-SO winemaking has been around a lot longer – Jules Chauvet and Jacques Néauport, widely hailed as the godfathers of the natural wine movement, started experimenting in Beaujolais in the 1980s.

There’s little doubt that making wine without adding any sulphites is a high-wire act. Producers who succeed tend to be those with considerable experience. The results can be stunning in their clarity and character, but for most winemakers, the unpredictability and risks of spoilage or instability are simply too great. Keep a keen eye on those pushing the boundaries though – their wines might just surprise you.

EU limits for SO2 usage

Dry red wine – 150mg/l

Dry white and rosé wine – 200mg/l

Red wine with 5g/l sugar or more – 200mg/l

White wine with 5g/l sugar or more – 250mg/l

Spätlese – 300mg/l

Auslese – 350mg/l

Trockenbeerenauslese, Beerenauslese, Sauternes – 400mg/l

Since 2012, permitted limits in organically certified wines are 30mg/l less in each category

Writer, columnist and natural wine specialist Simon Woolf won the 2015 Born Digital Award for best editorial/opinion wine writing

Translated by Sylvia Wu / 吴嘉溦

All rights reserved by Future plc. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of Decanter.

Only Official Media Partners (see About us) of DecanterChina.com may republish part of the content from the site without prior permission under strict Terms & Conditions. Contact china@decanter.com to learn about how to become an Official Media Partner of DecanterChina.com.

Comments

Submit